Over the past six years, Latin America and the Caribbean have met the basic conditions that guarantee freedom of expression and freedom of the media, though the situation has not been even in the 33 countries that form part of the region…

UNESCO*/ Regional, August 2014

Overview

Over the past six years, Latin America and the Caribbean have met the basic conditions that guarantee freedom of expression and freedom of the media, though the situation has not been even in the 33 countries that form part of the region (1). Even in the countries that have strong legal frameworks that regulate this area, implementation continues to be a challenge.

Several Latin American nations have approved new laws on the media. For some, this represents an opportunity to transform the media landscape into a more pluralist and less concentrated sphere. For others, it is an opportunity for governments to act against the media outlets that criticize their efforts. This discussion also has been reflected in cases in which steps have been taken to revisit obsolete laws, such as those inherited from military dictatorships. There has also been a trend on the part of public officials to initiate criminal actions against journalists and media outlets, though in most cases such efforts have not prospered. The countries that have historically upheld international standards of freedom of expression and access to information maintained this trend.

Legal/ Regulatory Context

With just one exception, all of the countries in the region have constitutional guarantees or laws that protect freedom of expression as a fundamental right. The cases of censorship that had been observed in the past are infrequent. Over the past few years, there has been a tendency to reformulate existing regulations or to create new laws or standards on the media. At least 19 countries have carried out such actions or have announced the intention to do so. In some cases, these reforms have been introduced in contexts of open conflict between the government and the media regarding which public opinion has been divided. Critics sustain that in some countries the new regulations are increasingly being utilized to restrict opposition voices through the closure of media outlets even though officials claim that these closures are due to a lack of compliance with radio and TV transmission standards, such as operating without a license or failure to pay the appropriate fees.

Over the past few years, the Special Rapporteur for Freedom of Expression of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR), which forms part of the Organization of American States (OAS), has recommended the elimination or amendment of laws that criminalize contempt, defamation, libel or insult and has encouraged countries to adapt their legislation in order to guarantee access to public information. A proposal to reform the IACHR that has been supported by a few countries and could have weakened the Special Rapporteurship for Freedom of Expression was rejected by the OAS General Assembly.

There is a region-wide tendency to decriminalize defamation, and three of the seven countries that have introduced this change over the past few years are Caribbean nations. There is now a tendency towards the abolition of laws against contempt which specifically refer to the defamation of public officials. However, during this same period, there have been no major changes in regard to the use of other charges such as civil defamation and libel on the part of officials or powerful citizens to restrict information regarding matters of public interest. The OAS Special Rapporteur has expressed concern regarding the use of crimes of “terrorism” and “treason” given that it violates the right to freedom of expression of those who criticize governments.

The media that require licenses to operate face a situation of vulnerability given that the expiration and renewal of licenses can be used to exercise political pressure. This trend is particularly noteworthy in a few specific countries. There have also been attempts to limit the written press. Some countries have approved new regulations regarding the importation, sale and/or distribution of newspaper which, according to some critics, opens up the possibility of indirect government intervention in the written press. Community radio stations have played an important role in some nations because they transmit local news and programs using popular language, but they have only begun to benefit from legal-regulatory frameworks in the past few years.

The Internet has increasingly become the focus of attention of legislative initiatives through specific media for this platform and all media platforms. In many cases, the legislation has been interpreted as covering cases involving the Internet. These trends can be observed in bills that seek to protect the intellectual property rights through the elimination of specific contents, in requests by governments to eliminate certain contents, and in judicial actions that limit and restrict access to content that is considered offensive or the use of prison sentences to punish journalists or bloggers who obtain and publish “secret” information. These could be signs of the emergence of a tendency towards censorship of information published online.

Some countries have included dispositions regarding the use of and access to the Internet in their general media laws. In the majority of countries in the region, the inclusion of legislation to allow contents to be filtered has been discussed, but at this point the groups that promote more openness have more support. The tradition of filtering contents related to child pornography persists in the region. In cases that could be incompatible with international standards, the main motivations invoked when eliminating contents have been political issues, defamation and intellectual property despite the generalized absence of regulations that allow for such action to be taken. On the other hand, there has been a compensatory tendency towards the adoption of proactive legislation for the codification of Internet rights. In 2010, Chile was the first country in the region to approve legal dispositions to guarantee “net neutrality,” and Brazil developed a Civil Internet Framework that was presented to Congress.

The media in Latin America and the Caribbean engage in investigative journalism, though there is a great deal of variety in the quality and impact of the work depending on the size of the media and place of production. This type of journalism has been more frequent in media companies located in large capital cities, in part due to the lack of formal training provided to journalists who work in rural and remote areas. In general, the region continues to have media with sufficient capacity to engage in investigative journalism on public and private interests. In recent years, the investigative journalism associations have become key organizations in the uncovering of public interest stories and for providing journalists with resources. (2)

Throughout the region, the right to protect sources has been recognized. This is supported by the Declaration of Principles on Freedom of Expression of the IACHR and the Chapultepec Declaration of the Inter-American Press Society. The majority of the countries in the region offer legal protection for sources and six include this right in their national constitutions. However, such laws do not exist in Caribbean nations.

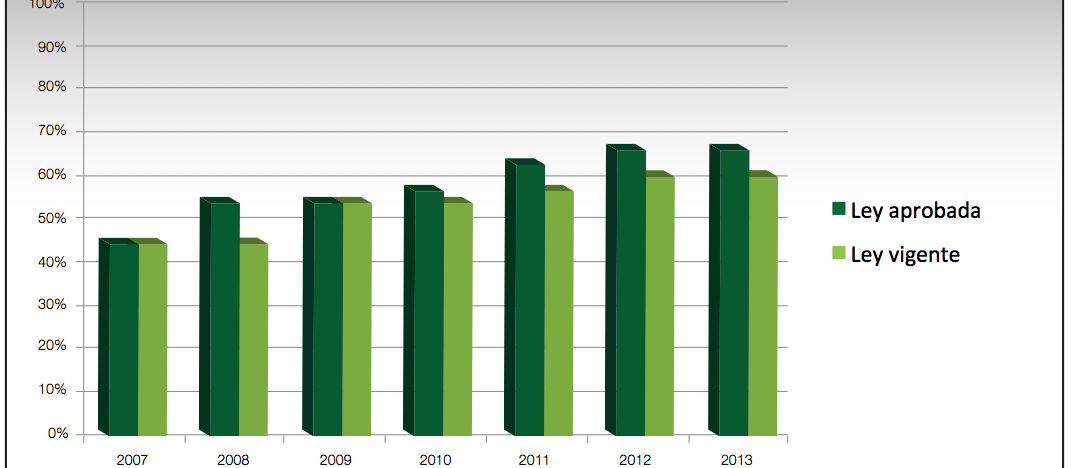

On the other hand, there has been a strong trend towards greater transparency in the region. Over the past six years, freedom of information laws have been promoted in a sustained manner and have been approved in six countries, bringing the regional total to at least 18 including five Caribbean nations. Though many countries had legal mechanisms in place that guaranteed this right, the new laws brought the mechanisms under a single umbrella, giving them coherence and broadening their reach. The OAS has developed a model law on access to information in order to “provide governments with the legal foundations necessary to guarantee the right to access to information.” The region also has shown its support for the Open Government Alliance, a global strategy with governmental support that is directed at promoting a culture of transparency. Since 2011, 15 countries in the region have supported this initiative. The transparency laws and initiatives have generated greater opportunities for engaging in quality journalism in the region.

Figure 1

Member states with freedom of information laws: Latin America and the Caribbean

Sources: Consensus list of 93 countries with freedom of information laws or the equivalent, www.freedominfo. org (March 2013); Fringe Special: Overview of all FOI laws, Vleugels, R. (30 September 2012); List of Countries with Access to Information (ATI) Provisions in their National/Federal Laws or Actionable Decrees, and Dates of Adoption & Significant Amendments, Open Society Justice Initiative (March 2013).

However, there has been a gap between the freedom of information laws and their implementation. There also seems to be a trend on the part of governments to adopt freedom of or access to information laws and then try to dilute or weaken those measures. In general, this situation has been unequal in the region. In 2012, Colombia became the first country to introduce a form of assessing this through the creation of the Index of Freedom of Expression and Access to Information.

*Fragment from the report Tendencias mundiales en libertad de expresión y desarrollo de los medios: situación regional en América Latina y El Caribe. UNESCO, 2014. (Global Trends in Freedom of Expression and Development of the Media: The Regional Situation in Latin America and the Caribbean.)

Notes

-

Based on a longitudinal analysis developed using Freedom of the Press survey data, in the past six years the number of countries with “Free” and “Partially Free” media systems has decreased and the number of countries with media systems classified as “Not Free” has increased.

-

For example, the Brazilian Investigative Journalism Association, which was created in 2002, the Journalistic Information and Investigation Center created in Chile in 2007, the MEPI Foundation that was created in Mexico in 2010, and Guatemala’s Public Square, which was founded in 2011.